Recently added item(s)

No products

Product successfully added to your shopping cart

There are 0 items in your cart. There is 1 item in your cart.

Histoire - Etudes

- New Selection

- Books

- Music

- Videos - DVD

- Miscellaneous

- Revues, Journaux

Links

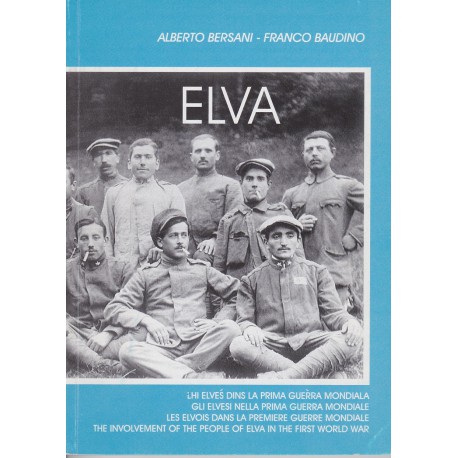

Elva (Lhi Elvès dins la prima guèrra mondiala) - n° 8 - Alberto Bersani - Franco Baudino

L-9999000000327

New

2 Items

Available

7,00 €

Elva (Lhi Elvès dins la prima guèrra mondiala) - n° 8 - Alberto Bersani - Franco Baudino. The involvement of the people of elva in the first world war. Chambra d'Òc.

Data sheet

| Type | Paperback |

| Year | 2005 |

| Language | Occitan, italien, français, anglais. |

| Pages | 96 |

| Format | 15 x 21 cm |

| Distributor | Chambra d'Òc |

More info

Elva (Lhi Elvès dins la prima guèrra mondiala) - Alberto Bersani - Franco Baudino

Gli elvesi nella prima guerra mondiale. The involvement of the people of elva in the first world war.

It was the 24th of May 1915, ninety years ago, and the Piave buzzed while Italy entered into what was to be defined the “first world war”. A devastating conflict which Pope Benedict the 15th would condemn as “useless slaughter”. It broke out in August of 1914, following the assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne...

Era il 24 maggio 1915, novantanni fa, e il Piave mormorava mentre l'Italia entrava in quella che fu definita "prima guerra mondiale". Un conflitto devastante che Benedetto XV condannò come "l'inutile strage". Le conseguenze furono tre anni e mezzo di lotta e di impegni durissimi, misurati dai 615.000 caduti.

Gli Elvesi conobbero la guerra andando a combatterla lontano da casa.

"A 19 anni sono partito da soldato con l'artiglieria alpina, I° reggimento. Sono andato sull'Ortigara, con i pezzi da 65 Skoda, sparavamo anche a zero con quei pezzi. Cosa pensavamo di quella guerra? ne capivamo niente; eravamo dei ragazzotti). Vivevamo come le talpe, se alzavi la testa le pallottole arrivavano come la tempesta. Mesi e mesi sempre nella stessa tana, era lí che era dura. Proprio una bella giovinezza".

50 fotografie in bianco e nero

Editions Chambra d'Òc.

Extract from the english version:

It was the 24th of May 1915, ninety years ago, and the Piave buzzed while Italy entered into what was to be defined the “first world war”. A devastating conflict which Pope Benedict the 15th would condemn as “useless slaughter”. It broke out in August of 1914, following the assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and immediately escalated like a relentless disease, as it turned out, it was incapable of resolving any of the problems. Instead, it brought many of them (some even now still unresolved), creating the preamble for the subsequent conflict that was to follow: the “second world war”, even more devastating, and truly involving the entire planet, without any distinction between soldiers and civilians. The consequentiality between the two tragedies justifies those historians who today consider the two conflicts as different chapters of a single great “30 year war”.

In April 1915, Italy was a signatory to the London Pact, allying it with France, Great Britain and Russia thus abandoning the Triple Alliance binding it to Austria and Germany. It was an about face which did nothing for the nation’s prestige, even if everything is relative in international relations. Inspired by interventionist nationalism, the new alliance sought justification in irredentism and in the hope of completing the Revival process with the liberation of Trento and Trieste from Austrian foreigners, without neglecting the vision of Italian expansion into the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean which the Pact provided for. The belief that the war, started the previous year and having reached a stalemate situation, would be over in a few months was also a factor: indeed, Italy’s participation would have decisively disrupted the equilibrium of the alliance and battlefield forces, in favour of the French – English. It was a mistake, for the remedy of which, Giolitti’s countermoves were not sufficient.

The consequences were three and a half years of hard conflict and struggle, gauged by the 615.000 fallen and the immense political, economic and social problems which, despite victory, would reappear during the post-war period, aiding the rise of fascism.

Beside this realistic interpretation of the First World War, there is another, more idealistic view. The conflict was seen as a holocaust and not a massacre; as the ransom for a population who, through combat, had regained national dignity and pride after centuries of servitude; like a crucible, where the Italy of the Revival would not only extend its borders beyond Trento and Trieste but forge together its thousands of regional and local identities into the unity which the countries founding fathers had dreamed; like an epic, in which the nation was seen to be capable of immense endeavour and coalesce together, both on the battle front and internally. [...]

The singularity of Elva – that enigmatic jewel where nature and art compete to outshine one another – has motivated a not inconsiderable number of publications. Hence, it is not very difficult to trace news of the events pertaining to its history: from its legendary origins (the four fleeing brigands) to the passing of the Romans (the walled stone outside the parish church), from the long period under the rule of the Marquises of Saluzzo to the arrival of Savoy rule. These were dependencies which did not impede the creation and maintenance of a strong sense of autonomy for several centuries, legitimised during the Marquis period by statutes, common throughout the middle and high valleys, and specifically for Elva, by the Franchisa Magna of 1475 defining the people of Elva “aborrentes servitutem et amantes libertatem instinctu naturali – natural abhorrers of slavery and lovers of liberty”.

History is accompanied by events, themselves also well documented, of a society, constrained by the geographical conditions, to long periods of isolation, but in itself, accordingly forced to organise itself, so as to be able to face every challenge, both natural and man-made. An isolation which curiously does not impede the people of Elva from devising professions – such as that of hair traders or collectors, almost unique in the world – taking them around Italy and Europe until establishing trade links with such locations as Paris, London, Berlin and New York.

However, the details won’t be discussed any further. Rather, it may be interesting to remember – no more than examples – what and how were the generation from Elva that came to live through the First World War: what were its mannerisms and experiences of life? The testimonies which Nuto Revelli has collected in his investigative books, from “The strong ring” to “The world of the vanquished” are of use in this. The latter in particular is a precious source of information. And from the pages of the above books, it is worthwhile extrapolating some passages from the narrative which Daniele Mattalia, a native farm-hand from Elva, class of 1897, tells to Nuto Revelli on the 3rd February 1973. It has everything.

[...]

Reviews

No customer comments for the moment.

Customer reviews

Precieux et riche.. Il faut encore éditer d'autres livres memoriels sur nos anciens de la montagne.

English

English Français

Français Occitan

Occitan